MSU Extension 2019 Health and Nutrition Statewide Needs Assessment

Background: The Montana State University Extension Family Consumer Sciences (FCS) program works to improve the lives of constituents by providing unbiased, research-based education and information to strengthen individual, family, and community well-being across the state. To understand how future efforts should be allocated across diverse Montana populations, a needs assessment was conducted with potential Extension participants.

Process: Participants (n=967) were recruited online and in-person to take a 17 question survey, with specific efforts to recruit non-Extension participants (56%), low-income families (36%), Native Americans (11.3% and 21+ tribes represented), and individuals representing all 56 counties.

Findings and Future Outreach: Respondents identified…

- good health and wellness as multi-dimensional with five main descriptions- physical, mental, holistic, self-care and enjoyment, and social health;

- top community resources supporting healthy lifestyles- often physical locations including farmers markets (71%) and indoor or outdoor recreational space (64% and 63%, respectively);

- top topics of interest- stress management (62%) followed by food preparation (61%) and physical activity (60%);

- top delivery formats of interest- traditional participation in group sessions in a

series (48%) or as a single session (44%), but additional newer technology driven

delivery formats had varying

popularity among potential participants; - five main barriers to a healthy lifestyle- time, access, finances, health conditions, and self-efficacy; and

- five main potential supports to a healthy lifestyle- people, community resources, technology, quality of life outcomes, and desired activities.

Additionally, this report highlights how responses varied for specific audiences.

Findings will help

to ensure FCS programming is responsive to the needs of Montanans.

Montana State University (MSU) Extension works to improve the lives of Montanans by providing unbiased, research-based education and information that integrates learning, discovery, and engagement to strengthen the social, economic, and environmental well-being of individuals, families, and communities. MSU Extension serves as the outreach branch of the three-part Land Grant University mission of teaching, research, and outreach with a central office on the Bozeman campus as well as presence in all 56 counties and 7 reservations. Within MSU Extension, the Family and Consumer Science (FCS) program area provides resources, support, and education in a variety of health and wellness areas and topics. Extension FCS programming first began in 1914 as a way to educate women, as they were critical influencers of individual, family, and farm wellbeing (Scholl, 2013). Currently, the FCS mission has expanded, aiming to impact the quality of life for individuals, families, and entire communities, by empowering and enabling well-being in physical and mental health, food and nutrition, family, finance and more to improve their daily lives and grow vibrant communities. In Montana, FCS resources are shared by the over 50 MSU Extension Agents, the 18 SNAP-Ed/EFNEP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education/Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program) Educators, and the 8 state content Specialists, in all of Montana’s 56 counties and 13 tribes, in collaboration with a variety of state partners.

Statewide statistics for health behavior trends and current conditions highlight areas where Extension outreach might impact common chronic and acute health challenges facing Montanans. For example, only 11% of adults in Montana reported meeting the daily fruit intake recommendations and even fewer (8%) are meeting the daily vegetable intake recommendations (CDC, 2019). For some Montanans, access to food may be a barrier to consuming the recommended amount of fruits and vegetables with 28 counties classified as food deserts, which are defined as ‘limited access to quality and affordable foods’ (ERS, 2019). Similarly, only 21% of Montana adults are meeting the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans aerobic and muscle strengthening recommendations (HHS, 2019). Montanans may have the knowledge and skills to be active but many (25%) have limited access to safe and affordable places to meet physical activity recommendations (CDC, 2019). These factors impact the health of Montanans - for example, 83% of adults 45 years and older report taking medication for high blood pressure (Montana CDPHPB, 2016), there was an increase of 300% of adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes between 1990 and 2015, and 63% of adults report they are overweight or obese (2018) (Montana DPHHS, 2019). In addition to physical health challenges, numerous Montanans face mental health challenges with 1 in 10 Montana adults reporting frequent mental distress, which is potentially contributing to nearly 64,000 Montana adults that are struggling with substance use disorders and an average of 240 suicide deaths each year in Montana (Montana DPHHS, 2019).

In light of the health behavior and outcome challenges facing Montanans and the MSU Extension mandate for research-based health improvement efforts across the state, the research team sought funding from MSU College of Education, Health, and Human Development and MSU Extension to identify Montanans health and wellness priority areas in a statewide needs assessment in 2019.

The purpose of the needs assessment was to meet the following objectives:

- Identify community needs and assets to support health goals across Montana;

- Identify desired supports and programming strategies for translating research into outreach, particularly for underserved and hard-to-reach potential Extension participants; and

- Inform future efforts in MSU Extension Food, Nutrition, Health, and Wellness (a subset of FCS) outreach, research, and resource allocation.

Based on the objectives above, the research team developed a seventeen-question needs assessment survey, which included demographic questions, multiple choice, multiple answer, and open-ended questions. Results for closed-ended questions are presented as a percent of respondents who chose each answer option. For open-ended responses, results were analyzed in NVivo software to code, group and theme responses. Participants who completed at least one of the open-ended questions beyond the initial demographic questions were included in analysis.

The survey was shared both electronically (via the Qualtrics platform) and in print from spring through summer of 2019. Participants were recruited through Extension and non-Extension email listserves, newsletters, social media platforms, or in person. After several months of data collection, preliminary data was analyzed in order to ensure representation from Montanans from various demographic groups (rural, Native American, men, young adults, etc.).Additional efforts were made to reach out to groups who were not as well represented. During the survey, participants could provide email or contact information, not connected to their responses, for an opportunity to win one of five, $50 Amazon gift cards. A total of 967 survey responses were included in this report.

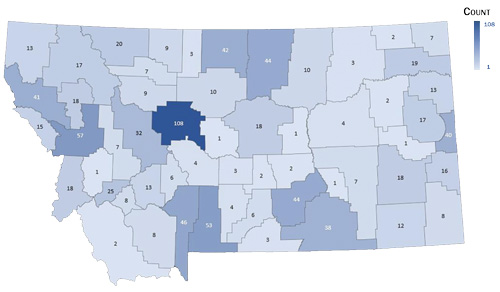

The 967 participants included one or more persons from all 56 counties and 13 tribes in Montana (see Figure 1). Both users and non-users of Extension completed the survey, with a higher percentage of survey respondents (56%) having never used Extension services. Figure 2 highlights the demographic variations among survey participants. Researchers did not collect exact age or household income, instead allowing participants to self-select categories. Approximate income categories were based on reported household income categories by $10,000 and reported household size to determine which category a household might fall related to the 2018 Federal Poverty Level (FPL) guidelines. Participants living in the seven largest Montana towns by population were categorized as ‘urban’ (Billings, Missoula, Great Falls, Helena, Bozeman, Kalispell, and Butte) while all others were classified as ‘rural’.

Figure 1. Frequency of Survey Responses by County in Montana:

| Count/County | Counties with this number of responses |

| 1 | Granite, Judith Basin, Petroleum, Prairie, Treasure |

| 2 | Beaverhead, Daniels, Golden Valley, McCone, Musselshell |

| 3 | Carbon, Liberty, Valley, Wheatland |

| 4 | Garfield, Meagher |

| 6 | Broadwater, Stillwater |

| 7 | Pondera, Powell, Rosebud, Sheridan |

| 8 | Carter, Madison, SIlver ow, |

| 9 | Teton, Toole |

| 10 | Choteau, Phillips |

| 12 | Powder River, |

| 13 | Jefferson, Lincoln, Richland |

| 15 | Mineral |

| 16 | Fallon |

| 17 | Dawson, Flathead |

| 18 | Custer, Fergus, Lake, Ravalli |

| 19 | Roosevelt |

| 20 | Glacier |

| 25 | Deer Lodge |

| 32 | Lewis and Clark |

| 38 | Big Horn |

| 40 | Wibaux |

| 41 | Sanders |

| 42 | Hill |

| 44 | Blaine |

| 46 | Gallatin |

| 53 | Park |

| 57 | Missoula |

| 108 | Cascade |

| 967 | Total |

| 29 | Not identified or not MT zipcodes |

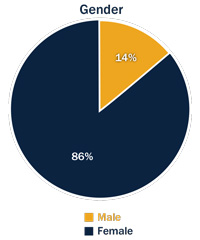

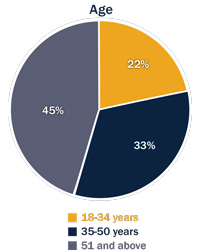

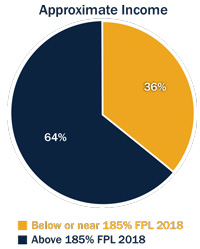

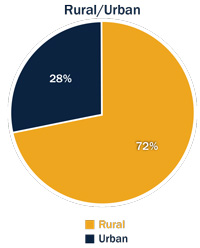

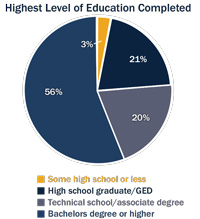

Figure 2: Demographic Information of Survey Respondents

Gender: 86% Female, 14% Male

Age: 22% 18-34 years, 33% 35-50 years, 45% 51 and above

Approximate Income: 36% below or near 185% FPL 2018, 64% above FPL 2018

Rural/Urban: 72% rural, 28% urban

Highest Level of Education Completed: 3% Some high school or less, 21% high school graduate (GED), 20% technical school/associate degree, 56% bachelors degree or higher

Participants were also ethnically diverse, which aligns well with the demographics of Montana as a whole (see Table 1). Those identifying as American Indian were also able to share their tribal affiliation(s) which included representation from all 13 tribes residing in Montana and more (see Table 2).

Table 1: Percent Comparisons of Respondent and Montana Race and Ethnicity

| Race & Ethnicity | Survey Respondents | Montana |

| American Indian | 11.3% | 6.5% |

| African or Black | 0.8% | 0.4% |

| Pacific Islander | 0.2% | 0.1% |

| Caucasian or White | 80.9% | 89% |

| Asian | 0.7% | 0.7% |

| Middle Eastern | 0.3% | n/a |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1.8% | 2.7% |

| Other | 1.1% | n/a |

Table 2: Frequency of Respondent Tribal Affiliations

|

Tribal Affiliation |

# Of Persons |

|

Assiniboine |

7 |

|

Blackfeet |

16 |

|

Cherokee |

1 |

|

Chippewa |

8 |

|

Cree |

9 |

|

Crow |

17 |

|

Dakota |

1 |

|

Eastern Shoshone |

1 |

|

Gros Ventre |

7 |

|

Kootenai |

6 |

|

Little Shell |

4 |

|

Mohawk |

1 |

|

Navajo |

2 |

|

Nez Pierce |

1 |

|

Northern Cheyenne |

6 |

|

Pend’Orielle |

1 |

|

Salish |

7 |

|

Sioux |

10 |

|

Anasazi |

1 |

|

Apache |

1 |

|

Other (Native, Alaska Native) |

4 |

Good Health and Wellness is Physical Health:

“Having a healthy diet, clean eating, and being active (raising your heart rate) for

an hour or more at least 5 days a week is essential to have the ground work for good

health. Good health and wellness means that your body as a whole is healthy- average

blood pressure, normal cholesterol levels, normal glucose levels, healthy weight,

etc.”

Mental Health: Many respondents talked about mental health as an important part of their health and wellness definition. While some indicated this meant being free from mental illness, others referenced emotional, and physiological abilities such as “being able to cope with stress,” or more broadly, “having a sound mind,” and “just being happy.”

Good Health and Wellness is Mental Health:

“Turning to constructive, rather than destructive, coping mechanisms during times of excess stress.”

Social: Some respondents also shared the importance of family and community relationships, from supportive networks to giving back to the community.

Good Health and Wellness is Social:

“Not just the absence of disease, but also abundant energy, feeling mentally and emotionally

whole and connected to community, having solid, loving relationships.”

Holistic: Many respondents went beyond just mentioning physical or mental health, and often referenced multiple types of health such as “mind, body, and spirit” together, indicating a more holistic understanding of health and wellness. Many respondents discussed the importance of balancing these multiple types of health together to have personal good health and wellness. Respondents also mentioned life purpose, spirituality, and social connection.

Good Health and Wellness is Holistic:

“A way of living where ALL aspects of one’s life is taken into account. Good health and wellness encompasses more than quality food and movement - knowing how to navigate stressors, healthy relationships, purpose, social connection, a handle on work and finances, spiritual connection, etc.”

Self-Care and Enjoyment: Respondents also expressed feeling well enough to enjoy and accomplish the activities

they would like to do. Respondents highlighted being able to take care of oneself

independently in daily activities

“walking without pain,” “keeping up with daily hygiene,” or “disease management” as

well as hobbies or preferred physical activities such as gardening or hiking.

Good Health and Wellness is Self-Care and Enjoyment:

“To be able to greet each day with enthusiasm, hope, inspiration. Take care of yourself first, so you can take care of everyone else. If you are sick and tired, no one benefits. My dad told me years ago, “you are number one”, and I never knew what that meant until recently; how could I be number one when I had children, a husband, a job to be responsible for and take care of. Now I know what he meant.”

PRACTICAL IMPLICATION: The range of responses to this question indicate that Montanans consider good health and wellness to have multiple important aspects. When programming can be designed to combine more than one definition of health and wellness, it may have broader reach and impact.

Respondents identified those health and wellness community resources that they believe would support their behavior change (specific examples were provided). Respondents were able to identify any number of these community supports(see Table 3 for results).The top 5 most frequently selected resources were all visible, tangible resources or physical locations.

Table 3: Community Resources, in Order of Frequency

| Community Resource | Percent |

| Farmers markets | 71% |

| Gym/indoor recreational space | 64% |

| Outdoor recreational space | 64% |

| Stores and/or food banks with healthy food options | 53% |

| Community or personal gardens | 46% |

| Worksite wellness programs | 39% |

| Health education resources | 38% |

| Informal/formal peer support | 32% |

| Community health event/class | 28% |

| Online or social media resources | 28% |

| School wellness programs | 22% |

Practical Implication: While all potential community resources could impact individual, family, and community health, individuals may be more likely to look for outreach supports to their personal wellness goals in physical spaces already associated with health. These locations provide good opportunities for MSU Extension to collaborate with partners to expand policy, systems, and environmental supports to health.

Survey respondents were asked to select which topic areas (specific examples were provided) they would be most interested in learning about. Findings suggest that participants are interested in a wide variety of health and nutrition topics (see Table 4 for results). While over 60% of participants indicated interest in stress management, food preparation and physical activity, other topic areas (such as family involvement, chronic disease prevention and management, and food safety) had less respondent interest.

Table 4: Preferred Nutrition and Wellness Topics, in Order of Frequency

| Topic | Examples of Topic Area | Percent |

| Stress management | Mindfulness, anxiety reduction | 62% |

| Food preparation | Cooking skills, quick healthy meals | 61% |

| Physical activity | Fun ways to move more at home or work, strength training | 60% |

| Weight loss | Sustainable weight management techniques, manageable lifestyle changes, small steps | 54% |

| Local foods | Navigating a farmer's market, eating and shopping locally, gardens | 49% |

| Nutrition | Balanced diet, eating according to MyPlate | 48% |

| Mental Health | Depression, anxiety, suicide prevention | 46% |

| Food preservation | Canning, freezing, fermentation | 43% |

| Food budgeting | Stretching your food dollars | 38% |

| Chronic disease prevention | Diabetes, hypertension, asthma | 37% |

| Family involvement | Engaging together with food and fitness | 34% |

| Chronic disease management | Caring for yourself and loved ones | 27% |

| Food safety | Safe temperature, time, storage and preparation strategies | 20% |

Practical Implication: All potential topics are still important to the FCS mission. Though, to further engage participants, programming might incorporate multiple topics together, with the more popular topic areas highlighted in advertisement and marketing.

In addition to topics of interest, respondents identified delivery methods they would be interested in using to learn about these topics (specific examples were provided, see Table 5 for results). Aligning with much of Extension’s historic FCS programming efforts, the most frequently preferred delivery format is still in-person sessions as well as electronic educational handouts/newsletters. Figure 3 dives deeper into the top delivery method to see how frequently respondents would be willing to attend an in-person series. Newer, technology-driven delivery methods had varying popularity, with respondents showing higher interest in online, self-guided programs and short how-to online videos while phone applications, text messaging and radio programming were less popular.

Table 5: Preferred Method of Information Delivery, in Order of Frequency

| Method of Delivery | Percent |

|

Participate in a series of in-person, group sessions |

48% |

|

Participate in a one time, in-person, group session |

44% |

|

Receive an electronic education handout/newsletter |

39% |

|

Participate in online, self-guided classes/programs |

39% |

|

Watch short how-to videos |

37% |

|

Receive a printed copy of an educational handout/newsletter |

36% |

|

Participate in online classes/programs with an instructor |

31% |

|

View social media posts |

30% |

|

Talk to a health professional in my community |

27% |

|

Browse online resources |

25% |

|

Use phone apps |

24% |

|

Receive regular text messages |

17% |

|

Hear information on the radio |

10% |

Figure 3: Preferred Number of In-Person Sessions

| Number of In-Person Sessions | Percent |

| One-Two | 46% |

| Three-Four | 16% |

| Five-Six | 6% |

| Seven or more | 2% |

| Regularly throughout the year | 21% |

| I would not attend | 10% |

PRACTICAL IMPLICATION: No method had more than 50%interest indicating that multiple delivery methods will be needed to reach individuals of varying demographics from across the state. Continued research is needed to understand how preferred delivery methods can be used to best promote health and wellness behavior change.

abilities, while others described the challenges of managing and prioritizing daily resources towards achieving their health goals. Five main barriers emerged from their responses:

Time: Respondents have many real and perceived demands on their time, from family obligations to feeling too busy for healthy cooking and adequate physical activity.

Access: Across communities, respondentidentified limited ability to access physical activity opportunities and healthy food. Some shared that weather, geographic distance, or small community size impacted the availability or type of resources they were able to find locally.

Finances: Respondents discussed general challenges of money and budgeting, specifically considering the high costs of fresh or healthy foods, as well as fitness memberships or classes.

Health Conditions: Some respondents shared physical health limitations such as chronic disease or pain from movement, while others described less visible challenges from lack of energy or fatigue, stress, or mental health conditions like anxiety and depression.

Self-efficacy: Respondents described hurdles to their perceived ability to achieve their health goals,

referencing their perceived lack of control over

motivation, behavioral “bad habits”, and lack of support from others around them.

Access and Finances are barriers:

“We live more than 20 miles from the nearest town, so I can’t reasonably visit the gym, go to events, etc. The cost of healthy food is VERY high here. I work and drive 2 + hours a day so it is very difficult to fit in any extras (like working out, etc.).”

Health Conditions are barriers:

“Knee pain makes it hard to walk.”

Time is a barrier:

“Working 40 hours per week and trying to balance the needs of elderly parents and grandchildren create time constraints that make it difficult for me to plan meals and get the exercise that I need.”

Self-Efficacy is a barrier:

“Maintaining will power and goals during social events.”

Respondents also shared two or more supports that motivate them to live a healthy lifestyle. Some shared external supports, while others shared internal motivators that encouraged healthy activity or provided them accountability to either themselves or others they love. Supports also provided opportunities for self-improvement through skill building, knowledge growth, or fulfillment of future life goals. Five main supports emerged from their responses:

People: Almost all respondents mentioned other people as supporting them. People were mentioned both generally and specifically, and included family (spouses, children, grandchildren), friends, or peers as motivators.

Community Resources: Respondents listed resources ranging from locations like farmers markets, gardens, gyms, or health care facilities, to services like fitness classes, nutrition plans, specific health care professionals and/or accessessible outdoor opportunities.

Technology: Respondents also talked about technology resources, such as using health tracking apps or social media, to help them connect with people, track, and learn about health behaviors.

Quality of Life Outcomes: Many respondents included their desire for a good quality of life, from a desire to maintain or improve their current physical or mental health to avoiding disease, pain, or injury. Many respondents also talked about their desire to ‘generally be healthy’ while moving into the future as they age.

Desired Activities: Many respondents mentioned things that they wanted to be able to do, or goals they wanted to achieve, as a driver for them to live a healthy lifestyle. Examples included specific types of exercise, traveling, cooking for oneself, gardening, ability to keep up with children, or being able to comfortably fit into their clothes. Ability to succeed in these outcomes encouraged respondents to keep working on healthy behaviors.

Technology is a support:

“I gain inspiration from friends through social media, to try new foods or activities.”

People are supports:

"Knowing how important it is, maintaining health for myself as well as those who depend upon me.”

Desired Activities are a support:

“I feel my best when I have healthy habits, I’ve seen first hand the effects of chronic disease on a person’s life and I don’t want that to happen to me.”

Community Resources are a support:

“I love that the community has exercise classes to help me be active and stick to somewhat of a routine.”

All of the previous findings have been presented as an average of all responses, across all demographic groups that responded to the survey. The next section digs deeper into different demographic viewpoints, to better understand how or where MSU Extension nutrition and wellness programming can reach specific audiences.

This section highlights the community resources, topics, and delivery methods where respondents from a specific demographic reported unique variations differing from the overall state rankings or other demographic subgroups. These findings can help strategize ways to engage with specific demographic populations across the state and can be taken into consideration when planning outreach opportunities to potentially increase impact among these various groups of previous and/or future potential MSU Extension audiences. Based on survey results, here are some unique strategies for reaching the following groups of participants:

Native Americans:

- Much more interested in receiving printed copies as a delivery method compared to state overall averages.

- More interested in food safety topics compared to any other demographic subgroup and 2x’s as much interest compared to the state overall average.

- More interested in chronic disease management and prevention topics compared to other demographic subgroups and the state overall average.

- More frequently reported community health events as supportive community resources compared to any other demographic, and much more frequently compared to their non-native counterparts.

A Crow woman shared how her health goals were supported with chronic disease in mind: “I don’t want to be diabetic and I want my son to be healthy.”

Individuals with children in the home:

- Much more interested in mobile delivery methods like phone apps, social media, and text messages as compared to their counterparts with no children in the home.

- Much more interested in school wellness programs, family involvement, and food budgeting topics compared to their counterparts with no children in the home.

A parent of three children shared how "social media peer pressure" was a support to their health goals.

Individuals without children in the home:

- Much less interested in mobile delivery methods like phone apps, social media, and text messages compared to their counterparts with children in the home and other demographic subgroups.

Rural:

- Much more interested in receiving electronic copies as a delivery method compared to their urban counterparts.

- Less frequently reported community or personal gardens as resources compared to their urban counterparts.

Low-Income:

- More frequently reported stores and/or food banks with healthy food options as resources compared to overall state averages and much more compared to their higher income counterparts.

- More interested in receiving printed copies as a delivery method compared to overall state averages and much more compared to their higher income counterparts.

- Much more interested in food budgeting and food safety topics compared to their higher income counterparts.

- Much more interested in mental health topics compared to their higher income counterparts.

Although healthy food options could be a support, one low-income Montanan shared the current barrier of “cost and availability of good qualty, fresh vegetables in the local grocery store.”

Urban:

-

More interested in short how-to videos as delivery methods compared to state overall averages.

- Much more interested in talking to health professionals and browsing online resources compared to their rural counterparts and other demographic subgroups.

- Much more frequently reported outdoor recreational space as resources compared to their rural counterparts and other demographic subgroups.

- More interested in local foods and food preservation topics compared to their rural counterparts.

One woman from urban Missoula County described good health and wellness to mean “options and access to local, sustainable foods; [eating a mostly] plant-based diet with locally-grown meat.”

Current non-Extension Users:

- More frequently reported school and workplace wellness as a resource compared to their Extension user counterparts.

- Much more interested in using phone apps as a delivery method compared to their Extension user counterparts.

- More interested in family involvement and food budgeting topics compared to their Extension user counterparts.

Current Extension Users:

- Much more frequently reported community or personal gardens as resources compared to their non-Extension user counterparts.

- More interested in nutrition topics compared to their non-Extension user counterparts.

- More interested in in-person, series and one-time classes as a delivery method compared to their non-Extension user counterparts.

One current Extension user stated that “attend(ing) a great SNAP cooking class” was a support to her health goals.

Lower Education:

- More interested in receiving printed copies as a delivery method compared to state overall averages.

- Much more interested in weight loss topics compared to most other demographic subgroups.

- Much less frequently reported outdoor recreational spaces and community/personal gardens as resources compared to their counterparts with higher education.

Higher Education:

- Much less interested in physical activity or food safety topics compared to all other demographic subgroups.

- Much less interested in receiving printed copies as a delivery method compared to all other demographic subgroups.

- Much more frequently reported workplace wellness as a resource compared to most other demographic subgroups.

One woman with a bachelor’s degree or higher shared her health goals were supported by “my work letting me flex my lunches so I can workout [and] commuting by bikein the warmer months.”

Younger Adults:

- More interested in social media posts, short how-to videos, electronic copies, and phone apps as a delivery method compared to state overall averages.

- Much more frequently reported both indoor and outdoor recreational space as resources compared to their older counterparts and most other demographic subgroups.

- Much more interested in food preparation and food budgeting topics compared to all other demographic subgroups.

- Much more interested in mental health, but much less interested in chronic disease

management and prevention topics compared

to all other demographic subgroups.

One adult between 18-34 years old described good health and wellness to mean “eating mostly real food, limited to no processed food. Spending a minimum of 20 minutes outside everyday. Knowing the best way to support your mental health and self care.”

Older Adults:

- Much more frequently reported informal or formal peer supports as resources as compared to their younger counterparts.

- Less interested in mental health and stress management topics compared to most other demographic subgroups.

- Less interested in mobile delivery methods like phone apps, social media posts, and text messages compared to most other demographic subgroups.

- One adult aged 51+ years old explained that “working out with other ladies and talking with friends” were important peer supports to their health goals.

- Statewide averaged and themed responses (pgs 6-11), the variations by demographic group (p. 12-14), and the stories and anecdotes which community members shared (throughout report) highlight potential statewide FCS programming goals and opportunities to expand impact and reach.

- Although data is not representative for individual communities, these statewide findings can be a starting point for local conversations about priorities, preferences, and resources.

- The results of this needs assessment can help identify policy, systems, and/or environment outreach efforts that may meet the current needs of more Montanans.

- To ensure FCS health and wellness programming is adapting and responding to changing needs, the research team suggests that a similar statewide needs assessment should be conducted every five years.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019, April). National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Data, Trend and Maps. Retrieved December 11, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/data-trends-maps/index.html

Economic Research Service (ERS). (2019). Food Access Research Atlas. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/

Health and Human Services (HHS). (2019, February). Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Retrieved March 2019, from https://www.hhs.gov/fitness/be-active/physical-activity-guidelines-for-americans/index.html.

Montana Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Bureau (CDPHPB). (2016, August).

Montana Quick Stats. Department of Public Health and Human Services.

https://dphhs.mt.gov/Portals/85/publichealth/documents/Cardiovascular/MTQuickStatCurrentlyTakingHTNMedsAug2016.

pdf?ver=2018-09-24-155653-923

Montana Department of Health and Human Services (DPHHS). (2019). Priority Area 1: Behavioral Health. Retrieved January 5, 2020, from https://dphhs.mt.gov/ahealthiermontana/ (link updated as of January 2023 with changed weblinks at https://dphhs.mt.gov. Original link was: https://dphhs.mt.gov/ahealthiermontana/behaviorialhealth)

Scholl, J. (2013, Fall). Extension family and consumer sciences: Why it was included in the Smith-Lever Act of 1914. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 105(4), 8-16.

For more information contact:

Carrie Ashe, MEd

Nutrition Education Program Director

SNAP-ED & EFNEP

Montana State University

Extension

P.O. Box 172235

Bozeman, MT 59717-2235

406-994-2015

carrie.ashe@montana.edu

Michelle Grocke, Ph.D

Health & Wellness Specialist

Montana State University

Extension Assistant Professor,

Health & Human Development

P.O. Box 173370

Bozeman, MT 59717-3370

406-994-4711

michelle.grocke@montana.edu

Brianna Routh, Ph.D, MPH, RDN

Food & Family Specialist

Montana State University

Extension Assistant Professor,

Health & Human Development

P.O. Box 173370

Bozeman, MT 59717-3370

406-994-5696

brianna.routh@montana.edu

Suggested Citation:

Routh, B. Grocke, M. & Ashe C. (2020). Montana State University Extension 2019 Health and Nutrition Statewide Needs Assessment. Montana State University Extension. https://msuextension.org/wellness/needs_assessment

View online: https://www.montana.edu/extension/wellness/needs_assessment/index.html

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Montana State University and Montana State University Extension prohibit discrimination in all of their programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital and family status. Issued in furtherance of cooperative extension work in agriculture and home economics, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Cody Stone, Director of Extension, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717