Reasons Not to Feed Deer

In Montana, the winters can be particularly long and hard. This can take a toll on wildlife populations, especially deer. Deer can starve to death during winter and this could lead well-meaning people to consider providing food to ‘help’ deer survive. However, it is important to resist the urge to feed deer during these difficult times.

FEEDING DEER IS ILLEGAL

First and foremost, it is illegal to provide supplemental feed to deer and other big game in Montana (see state statute 87-6-216). Secondly, feeding deer can alter behavior and create a variety of unintended consequences, including increased fatalities. Supplemental food sources can render deer dependent upon artificial food sources (Figure 1), attract other wildlife, result in deer-caused damage on neighboring properties, increase the likelihood of deer/vehicle collisions, and cause a rise in deer population that opens up another suite of potential issues (over-browsing, disease transmission, etc.)

Figure 1. Illustration of some of the unintended consequences (e.g., abnormal concentration of deer and/or dependency on an artificial food source) that can occur from providing deer with a supplemental food source. Photo: Buck Manager – White-tailed Deer Management & Hunting. Photo: Buck Manager – White-tailed Deer Management & Hunting

MORE HARM THAN GOOD

In addition to the unintended side effects, feeding deer can actually have negative effects on their health. Introducing a new food to deer, particularly a high-energy food such as corn or high-protein food such as alfalfa hay, while their bodies are struggling during winter is a shock to their system, and at times even deadly. Deer digestion involves protozoa and bacteria that help break down food. Different microorganisms help digest different types of vegetation. If a deer has been feeding on aspen or willows, and suddenly fills its stomach with corn or hay, it may not have enough of the corn- and hay-digesting microorganisms in its stomach to digest the food. Meaning, a deer can starve to death with a full stomach (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Deer discovered near South Hampton, N.H. in 2015 that were suspected to have died from enterotoxemia; a condition caused by a rapid change in diet often associated with winter feeding. Photo: New Hampshire Fish and Game Department.

In addition, deer can become fixated on a food source. Deer will stay near a sure food source, even an inadequate one, rather than seek more sufficient food in other areas. Once food is discovered, deer concentrate around a feeder rather than scattering through the available winter range. Often, they remain in an artificial feeding area getting only half the food they need rather than fighting the snow to use natural browse. They quickly deplete any nearby forage and can stay in a feeder area until they starve to death. Springtime often reveals concentrations of dead deer within the immediate vicinity of feed areas.

Even in states where providing supplemental feed is legal (which again, is not the case in Montana), any interruption, whether due to depleted funds, personal illness, a vacation, a snow storm or a midwinter move to a warmer climate, will eliminate part or all of a deer’s diet and the deer that depend on you for food will suffer. The best way to avoid these adverse effects is simply to avoid any feeding in the first place.

Another concern with providing supplemental feed is the fact that food resources during a time of extreme stress will make deer abnormally competitive. Translation: deer won’t “divvy up” feed equally even if food is provided in abundance. Competition between deer in natural situations is usually limited because natural food sources are scattered. In artificial feeding situations, deer often become combative, striking one another with hooves to assure themselves a share of the food. The ones that need the food most (i.e., young, old, sick, in poorest health), are kept away by larger or stronger deer.

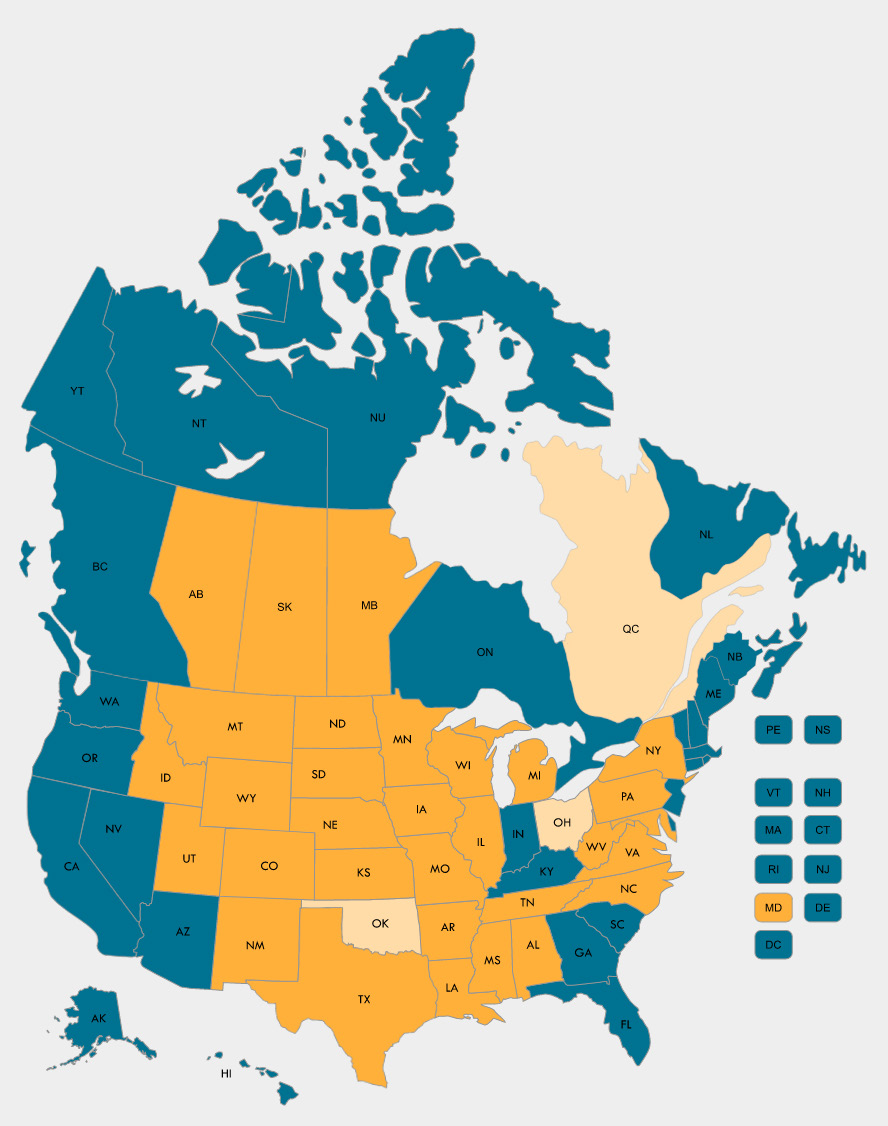

Artificial feeding can also spread disease. When deer are abnormally close to one another (Figure 1), contagious diseases or parasites are more easily spread. This is a major concern with Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD), which is fatal when contracted by deer, elk, and moose. CWD is a disease of increasing concern, with significant challenges for wildlife managers attempting to control or eradicate the disease (Figure 3). Clinical signs of CWD may be slow to develop and some individuals may not show any signs of the disease for years after they become infected. However, as CWD progresses, infected animals may have a variety of changes in behavior and appearance, which may include weight loss, stumbling, wide stand, lack of coordination, listlessness, excessive drooling, drooping ears, and/or lack of fear of people.

Figure 3. Map illustrating current distribution of Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD). States and Provinces in orange and tan have known cases of CWD as of 2021. Photo: cwd-info.org

If you do find deer that appear to be dying of starvation and/or showing signs consistent with that of CWD (Figure 4) report it immediately to the local Fish, Wildlife & Parks office.

TOUGH LOVE, NOT FOOD

Artificially feeding deer in winter can alter deer behavior and have detrimental, and sometimes fatal, effects. What deer need over winter months is “tough love” not food. The best way to help wildlife make it through the winter is to step back and allow the animals’ instincts to take over. To help wildlife near a home, focus on improving the wildlife habitat on or near the property by including natural food and cover (e.g., some conifer cover and regenerating forest or brushy habitat). It is also important that wildlife populations are in balance with what the habitat can support. It’s the only way to minimize starvation and work for both deer health and humane treatment.

Figure 4. Deer shows classic clinical signs of chronic wasting disease: emaciation, wide stand, lowered head, and droopy ears. Photo: Wyoming Game and Fish Department

Jared Beaver is the MSU Extension Wildlife Specialist.