Understanding Alzheimer's Through Storybooks

Were you aware there are more than 22,000 Montanans living with Alzheimer’s? Did you know 25 percent of Alzheimer’s caregivers also raise minor children? This means an increasing number of Montana children are experiencing and interacting with someone such as a grandparent who is living with Alzheimer’s.

People with Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia tend to repeat stories and express

paranoia or suspicious beliefs. They may wander or become agitated and may not recognize

their family members in

the later stages.

These symptoms can be upsetting and difficult for children to understand. Children

may choose to spend less time with the relative living with Alzheimer’s and experience

less emotional attachment. They may show signs of anxiety and confusion when they

are around the person. Additionally, they may feel scared, guilty, and upset. If the

relative lives with the child’s family, then the child may become embarrassed if their

relative displays odd behaviors while a friend is visiting.

Luckily, there are resources available to parents and caregivers to help their children cope with these experiences. Bibliotherapy is the practice of using storybooks to help children understand and cope with difficult issues. While the clinical bibliotherapy approach addresses trauma in clinical settings, parents, educators, and experts use developmental bibliotherapy to help support children’s social, emotional, and cognitive well-being and development. Choosing a suitable storybook about Alzheimer’s may seem difficult. However, asking certain key questions makes the choice easier. There are crucial ideas and questions to consider. Books depicting Alzheimer’s should help children understand and cope with the changes that Alzheimer’s brings to family life. The storybook should also support the maintenance of relationships between family members.

QUESTIONS TO ASK

- When selecting a book, ask the following questions:

- Does the storybook give straightforward and comprehensive Alzheimer’s information

for parents? Does it use diverse characters children can relate to?

- Does the storybook capture children’s experiences with a relative who has Alzheimer’s?

- Does the storybook show support from a parent or caregiver?

- Do the characters portray positive modeling, healthy coping skills, and positive communication?

Does the book’s character show common Alzheimer’s behaviors by the family member living

with Alzheimer’s?

- Does the book show supportive relationships between the child and the grandparents?

- Do the characters involved in the care of a relative living with Alzheimer’s explain

what they are doing and why?

- These questions can help select a book that portrays Alzheimer’s in a way your child

will understand.

Photo: AdobeStock

GUIDELINES FOR READING TO A CHILD

If you are a parent or caregiver who is reading a storybook to a child, there are

guidelines researchers have created to make the experience more effective.

First, focus on the specific issue or problem your child is facing. For example, a grandparent may show signs of forgetfulness and cannot remember the grandchild’s name. Perhaps Grandma is crying because she wants to go home when she is already home. Grandpa takes a walk or drive and does not know the way home.

Second, identify the goals to achieve by reading a storybook about Alzheimer’s to

a child. The goal may be to reassure a child that the family member still loves them

or to provide them with ways to help the family member.

Third, select the proper storybook for the topic. Montana State University Extension

has a list of Alzheimer’s storybooks and reading guides at: montana.edu/extension/alzheimers/booksandreadingguides.html

Fourth, implement these activities when reading aloud to a child. For example, pick

an ideal time for you and the child to read each day. A fact sheet outlining recommended

practices is available at: https://www.montana.edu/extension/alzheimers/alzheimertraining/communitytrainingsession/handouts/reccommendedpractices.html

Fifth, plan for follow-up discussions and activities to help draw out the main concepts

or goals of the storybook. For example, in one Alzheimer’s storybook, the grandchild

made a memory box for Grandpa. In another, a grandchild decided to “tell grandma the

same stories over and over again because they were her favorite stories.”

When reading and discussing storybooks that show family experiences with Alzheimer’s, gains in knowledge may occur for both the reader and the child. Research shows there is an increase in positive attitudes and willingness to interact with a family member with Alzheimer’s dementia after an adult reads and the child hears the story.

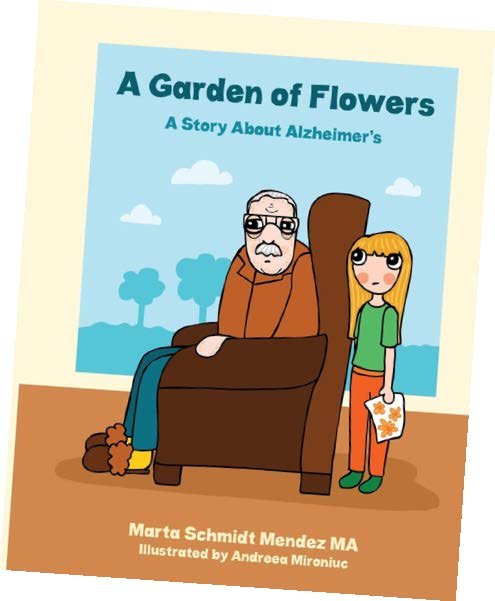

FREE ALZHEIMER’S STORYBOOK OFFER

MSU Extension is offering a free storybook about Alzheimer’s to individuals who read this article and would like to have a book to read to children. Go to this website (www.montana.edu/extension/alzheimers/), click on “Order Form for Free Storybook,” fill in your information, and use the promotional code “Alzheimer’s Storybook 1.”

Readers who do not have computer access can call 406-994-3511 to receive a free book. The authors express appreciation to AARP Montana and the Montana Geriatric Education Center at the University of Montana for providing funds to purchase storybooks to share with Montanans who want their children to understand Alzheimer’s.

Jennifer Munter is an MSU graduate student in Health and Human Development, and Marsha Goetting is a Professor and MSU Extension Family Economics Specialist.