Essay on 1968

[2016 November 9 (the day after the 2016 presidential election)]

--with additional edits and updates in 2017 and 2018.

The thoughts expressed here are my own: any errors or omissions are mine.

Robert C. Maher

Perspective. We all need some perspective on 2016, and what is to come.

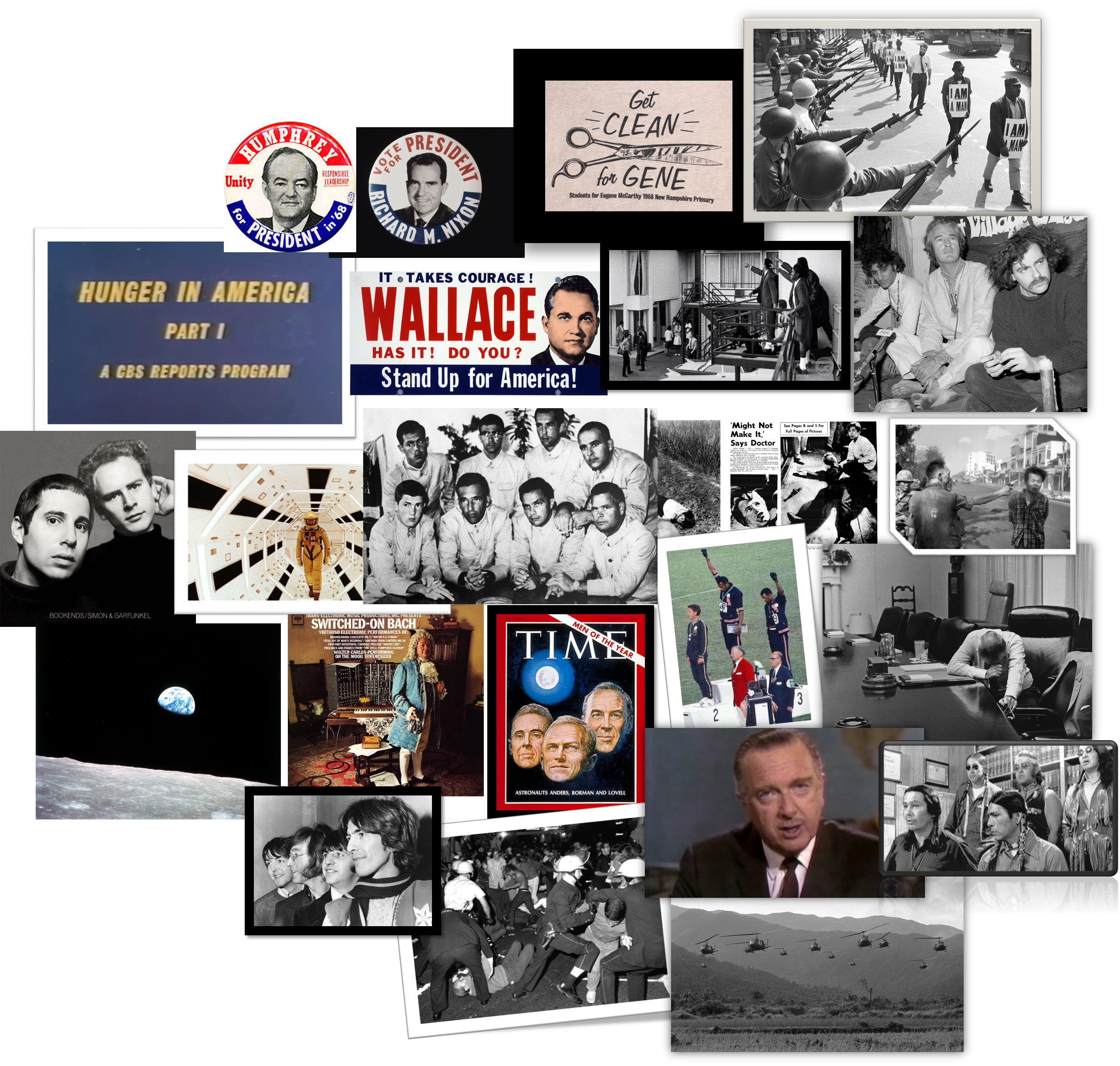

I recall my first experience with seeing political anguish and strife among adults, including my parents and my teachers: I was in kindergarten-first grade, and it was 1968. Remembering that time in American history helps put things in perspective--at least for me.

The year 1968 was a very tough one. The Vietnam War was in full swing, and the home front was ripping itself apart. People were openly thinking that America might not make it out of the year, much less the 1960s.

I grew up near Madison, Wisconsin, and my dad was a professor at UW. I remember in fall 1967 he came home from work and spoke of a riot that had taken place to protest the Dow Chemical job interviews taking place on campus. Dow was the manufacturer of Napalm. That riot was the start of campus radicalization that eventually culminated in the Sterling Hall bombing on the UW campus in 1970, killing postdoctoral researcher Robert Fassnacht. The bomb consisted of 2,000 lbs. of ANFO (ammonium nitrate and fuel oil). 25 years later, the Oklahoma City bombers used a similar but larger and more sophisticated explosive configuration.

1968 was a brutal year in America.

Early in January, 1968, North Korean patrol boats captured the USS Pueblo and its 83 member crew. All were eventually released 11 months later, but for most of the year the country worried about the crew and the potential for war with North Korea!

Then right at the end of January, 1968, 70,000 North Vietnamese troops unexpectedly launched the Tet Offensive, a major turning point in the progressively more critical attitude of the American people toward the war in Vietnam. A US army officer was quoted "It became necessary to destroy the town to save it," expressing the increasingly incomprehensible nature of the war. Walter Cronkite, highly respected managing editor of the CBS Evening News, traveled to Vietnam. Upon his return, Cronkite advised negotiation "...not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could."

President Johnson, facing a completely disintegrated Democratic party with multiple angry factions, announced on March 31 that "I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president." This left Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy as the Democratic candidates.

Also in March, more than 500 Vietnamese civilians were massacred by US ground forces at My Lai. The terrible incident did not become known publicly until November 1969.

On April 4, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Memphis. It was unbelievably sad and wrenching.

Vice President Hubert Humphrey entered the race for president on April 27.

Then in June, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles. There are no words.

Many felt that the entire country was falling apart...at least in 2016 we have not

had to cope with assassinations in our political realm--Lord have mercy upon us.

In August, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley ordered police to take action against demonstrators at the Democratic Convention. Hundreds were arrested and injured. Daley says: "The policeman isn't there to create disorder, the policeman is there to preserve disorder." Vice President Hubert Humphrey was the democratic nominee designated at the tumultuous convention.

Then in October the summer Olympic Games opened in Mexico City: Tommie Smith and John Carlos, U.S. medalists in the 200 meter run, gave a controversial black power salute during their medal ceremony. Disorder was everywhere, so it seemed.

George Wallace had entered the race for president as a third-party candidate, directly and openly appealing to alienated white voters. Richard Nixon, the Republican nominee, became concerned that Wallace would draw white conservative voters from Nixon's base, and Nixon and his running mate Spiro Agnew moved to manipulate their message to court the "silent majority" of middle and lower class white voters who were against the ongoing steps toward racial equality in America.

November came, and Richard Nixon was elected president. The "silent majority" movement played a significant role. That lesson was learned by the sequence of Republican presidential candidates who followed, and a similar message of courting alienated low-income and low-education whites was not lost this year (2016) on Donald Trump.

The one thing that "saved" 1968 for me--and in a significant way shaped my development into an engineer--was the drive to reach the moon by the "before this decade is out" deadline set by the late President John F. Kennedy

Throughout 1968 the NASA team and thousands of contractors were hard at work driving toward the goal of a successful moon mission before the end of 1969. The Saturn V booster had some problems but there was confidence those problems were understood and fixable. The command module, largely redesigned after the tragic Apollo 1 launch pad fire that killed astronauts Grissom, White, and Chafee in January of 1967, was also on track for the upcoming test missions. However, the lunar module was behind schedule and would not be ready for serious testing until early in 1969. The clock was ticking.

Christopher Kraft, NASA flight director, writes in his memoir:

That was when George Low [Manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office (ASPO)]

showed his genius. He spent a few days reviewing lunar module progress at the Cape

in late July and came home with bad news showing on his face. He usually hid his feelings.

Not this time. I'd never seen him so down.

Then he snapped out of it. A day or so later, he stuck his head in my door. "Chris,

I've got an idea about the moon. Do you have time to see Bob [Gilruth, head of the

Manned Spacecraft Center] with me?" [...] "What do you think about flying to the moon

without a lunar module? If Apollo 7 does okay in October, can we juggle the schedule

to fly a crew to the moon and back in December?"

His idea was a shocker. Gilruth leaned forward, elbows on his desk, and asked for

more details. "What kind of lunar mission? Just out and back, a circumlunar trip?"

"Yes, that's what I'm thinking," George Low said. "It would ace the Russians and take

a lot of pressure off Apollo. And we have to go there sooner or later anyway. I don't

think it makes much sense to fly twice in Earth orbit if we can go around the moon."

In just a matter of months, decisions were made and approvals received. The Apollo 8 mission would be late in December, and involve the first manned spacecraft to leave earth orbit and to orbit the moon. The astronauts assigned to the mission were Frank Borman (commander), Jim Lovell (command module pilot), and Bill Anders (lunar module pilot--although the mission did not include the LM).

The Apollo 8 launch was on December 21, 1968. A few days later the spacecraft successfully entered lunar orbit. The crew followed the flight plan and began taking photos of the lunar surface as it passed by 60 miles below their windows.

On the second revolution, Commander Frank Borman and astronauts Anders and Lovell were photographing the lunar surface passing below them. Then they happened to glance out a forward-facing window, and saw a stunning sight, as captured in the mission transcript:

Anders: Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! Here's the earth coming up. Wow,

is that pretty!

Borman: Hey, don't take that, it's not scheduled.

Anders: (Laughter) You got a color film, Jim?

Anders: Hand me that roll of color quick, will you - -

Borman: Oh man, that's great!

Anders: Hurry. Quick.

Borman: Gee!

Lovell: It's down here?

Anders: Just grab me a color. That color exterior. Hurry up! Got one?

Lovell: Yes, I'm looking for one. C 368.

Anders: Anything, quick.

Lovell: Here.

Anders: Well, I think we missed it.

Borman: Hey, I got it right here!

Anders: Let - let me get it out this window. It's a lot clearer.

Borman: Bill, I got it framed; it's very clear right here. You got it?

Anders: Yes.

Borman: Well, take several of them.

Lovell: Take several of them! Here, give it to me.

Anders: Wait a minute, let's get the right setting, here now; Just calm down.

Borman: Calm down, Lovell.

Lovell: Well, I got it ri - Oh, that's a beautiful shot.

Lovell: 250 at f:11.

Anders: Okay.

Lovell: Now vary the - vary the exposure a little bit.

Anders: I did. I took two of them.

Lovell: You sure we got it now?

Anders: Yes, we'll get - we'll - It'll come up again, I think.

Lovell: Just take another one, Bill.

The first photo was black and white.

{AS08-13-2329 - The first image of Earthrise taken by a human, with north at the top.}

The second photo, with a color magazine in the camera, became the famous 1968 "Earthrise" photo.

{AS08-14-2383 - Anders's first color image of Earthrise over the Moon.}

Many people attribute the acceleration of the environmental movement to the incredible impact of that amazing photograph: seeing the beautiful earth alone in the darkness of space, rising behind the stark, lifeless moon.

That evening, December 24, Christmas Eve, NASA scheduled an evening live TV broadcast from the astronauts circling the moon. The mission commander, astronaut Frank Borman, was a religious man, a lay reader in the Episcopal Church.

From the book "Apollo 13" by James Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger:

"We've been orbiting at sixty miles for the last sixteen hours," Borman said while

Anders pointed the lens downward at the surface, "conducting experiments, taking pictures,

and firing our spacecraft engine to maneuver around. And over the hours, the moon

has become a different thing for each one of us. My own impression is that it is a

vast, lonely, forbidding expanse of nothing that looks rather like clouds and clouds

of pumice stone. It certainly would not be a very inviting place to live or work."

"Frank, my thoughts are similar," Lovell said. "The loneliness up here is awe inspiring.

It makes you realize just what you have back on Earth. The Earth from here is an oasis

in the vastness of space."

"The thing that impressed me the most," Anders took over, "was the lunar sunrises

and sunsets. The sky is pitch black, the moon is quite light, and the contrast between

the two is a vivid line."

[...]

The astronauts went on and on, and at home, audiences watched the new pictures and

heard the new words and took in as much as their senses and skepticism would allow

them to. Finally, it was time for the show to sign off. For weeks before the flight,

the three astronauts had debated the best way to conclude the broadcast from one world

back to another on the eve of the holiest day in the Christian calendar. Shortly before

launch day, a decision was reached, and attached to the back of the onboard flight

operations manual was a sheet of paper (fireproof, of course, always fireproof these

days) with a short script typed on it.

Anders, pointing the television camera out the window with one hand and holding the

script with the other, said, "We are now approaching the lunar sunrise, and for all

the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message we would like to send

to you.

"In the beginning," he began, "God created the Heaven and the Earth. And the Earth

was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep." Anders read

slowly for four lines, then passed the paper on to Lovell.

"And God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. And the evening and

the morning were the first day." Lovell read four lines of his own and handed the

paper to Borman.

"And God said, Let the waters under the Heaven be gathered together unto one place,

and let the dry land appear." Borman continued until he reached the end of the passage,

concluding with "And God saw that it was good."

When the final line was done, Borman put down the paper. "And from the crew of Apollo

8," his voice crackled down through 239,000 miles of space, "we close with good night,

good luck, merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth."

After such a tragic and wrenching year 1968, the editors of Time Magazine chose the Apollo 8 astronauts as "Men of the Year." In some small way, their words and the courage of the NASA managers helped restore hope in a post-1968 future.

So, with the memory of assassinations, riots, and war from 1968, I am very confident that our country will make it through this latest political scourge.