Why Did My Property's Taxes Increase? Part 2 (Series on Property Taxation in Montana)

October 2, 2024

By Greg Gilpin

Overview

Montana homeowners experienced a significant shock when they opened their 2023 property tax bills, many facing steep increases compared to prior years. According to the Montana Free Press, the “median residential properties in Montana saw a 21% higher tax bill following this year’s reappraisal cycle.”

This post explores the factors driving these increased property taxes. I highlight six key mechanisms that can cause property taxes to rise:

- New government spending.

- Increased existing government spending.

- Overall property values rise with fixed mill levies.

- Your property’s value increases while others’ values remain steady.

- Your property’s value holds steady while others’ values decline.

- Special assessments increase.

In addition, you’ll learn key principles of property taxation:

- Higher taxable values do not automatically lead to increased taxes - mills levied typically decrease in response.

- Higher taxable values increase taxes 1-to-1 for fixed mill levies.

- For fixed government budgets, when one’s property taxes decrease, another’s must increase by the same amount to maintain the budget.

This post relies on basic property tax concepts, such as market value, taxable percent,

taxable value, and mill levies. If you are unfamiliar with these terms, be sure to

review Part 1 of this series: Understanding Your Property’s Tax Statement.

An Increase in Overall Property Values Does Not Directly Increase Taxes

An overall increase in properties’ taxable value doesn’t automatically raise the taxes owed. Instead, tax jurisdictions typically adjust the mills levied to maintain consistent revenue.

Example

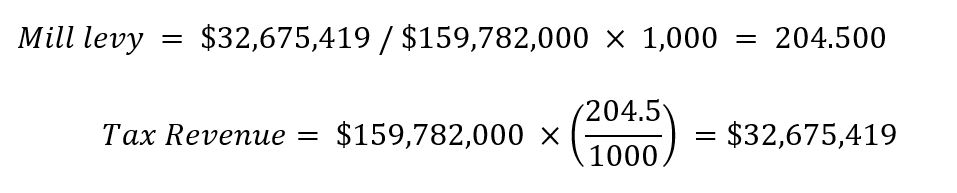

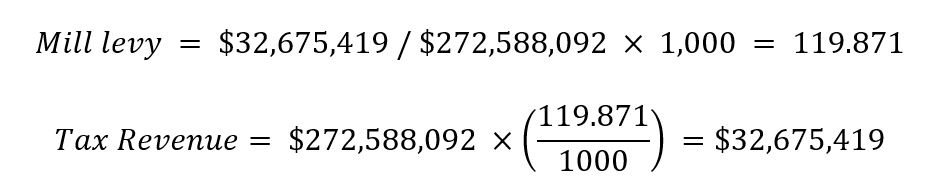

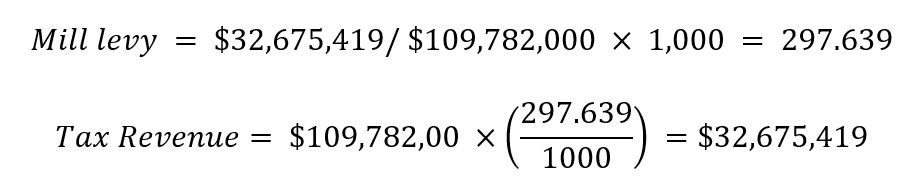

Suppose a city commission passes a budget of $32,675,419 for the year. If the total taxable value within the city is $159,782,000, the city will need to levy 204.5 mills to generate the necessary revenue:

For an example residential property with a taxable value of $6,187, the city taxes would be $1,265.24:

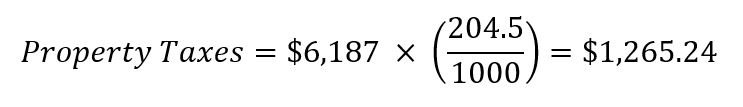

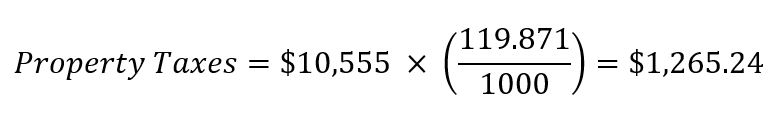

Now, let’s assume all values increase by 70.6%. The total taxable value is now $272,588,092 ($159,782,000 x (1.706)). To generate the same revenue, the city will need to tax properties at 119.871 mills:

The taxable value of the example property is now $10,555 ($6,187 x (1.706), and the property taxes will still be $1,265.24:

Key Principle of Property Taxation

The first principle of property taxation is that higher taxable values do not automatically lead to increased property taxes. Instead, the mills levied decrease to maintain the same revenue.

However, mills levied must adjust. Floating mill levies adjust in response to changes in property values, as shown in the example above. Fixed mill levies do not adjust. Most local government mills are floating, while State mill levies are

fixed, such as the 95-Mill Levy for public school fundinga, the 6-Mill Levy for universities, and the 1.5-Mill Levy for vocational colleges.

Why Do Taxes Rise If It Isn’t Due to Increases in Property Values?

Let’s explore the factors that can cause property taxes to increase:

1. New Government Spending

Local governments often use additional property taxes to fund new projects or services, typically approved by voters. This new spending can lead to higher property taxes.

Example

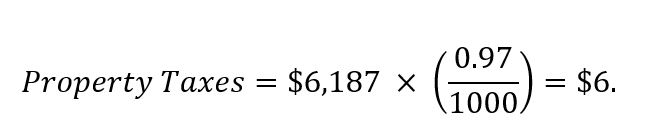

In 2021, Bozeman voters approved a $6.7 million 20-year bond to relocate Fire Station #2. This added a new levy of 0.97 mills to property tax statements, listed as BZN FIRE STN #2 GO BONDS. For a residential property with a taxable value of $6,187, this resulted in an increase of $6 in property taxes.

2. Increased Existing Government Spending

An increase in existing government spending leads to higher property taxes. This can happen for two primary reasons:

i. Increased Debt Payments for Approved Projects

Example

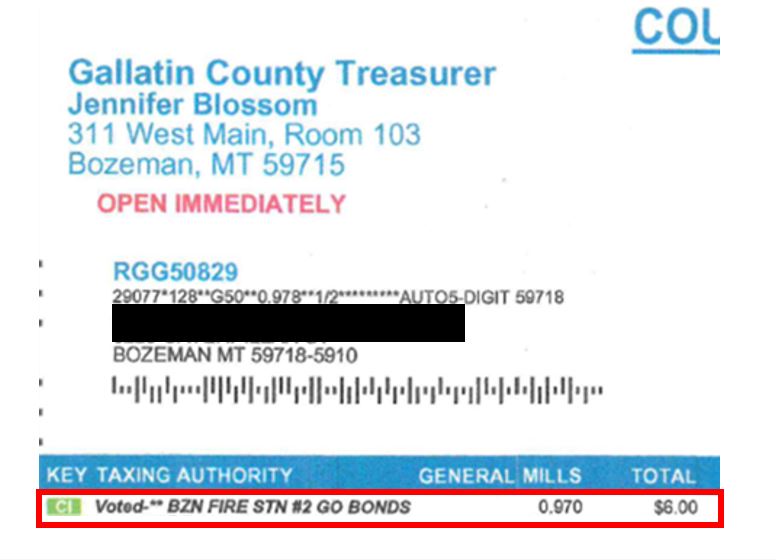

Bozeman's Fire Station #2 relocation required smaller debt payments in 2022 than in 2023. As construction progressed, debt payments increased, resulting in higher property taxes.b

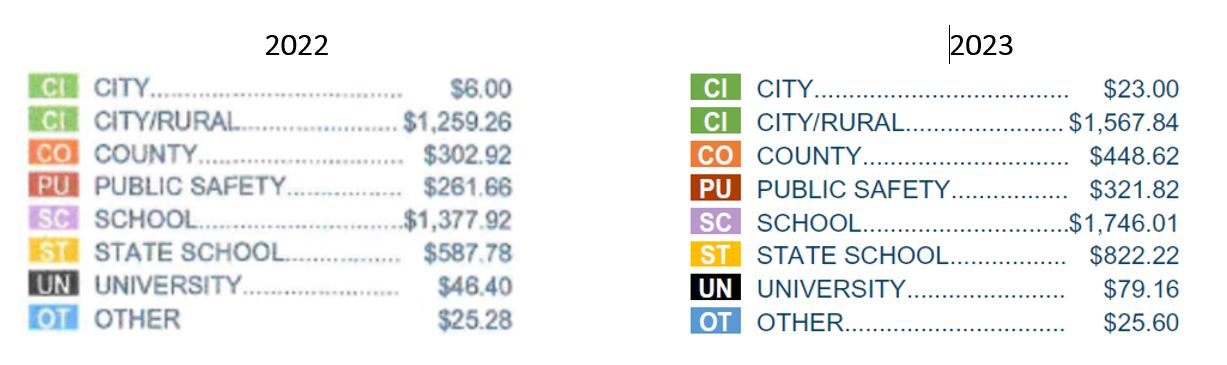

For the example property, the taxable value increased to $10,555 in 2023. The city assessed a tax of 2.18 mills to finance this debt, meaning the property owner pays $23 for the fire station, a $17 increase from the previous yearc:

ii. General Government Budget Increases

In Montana, local governments can increase their general budgets annually, but they are capped at 3% or half the rate of inflation, whichever is lower. When a local government increases spending, property taxes rise.

Example

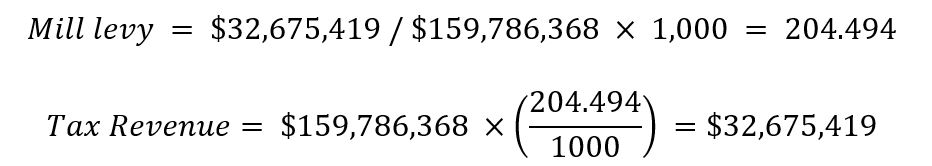

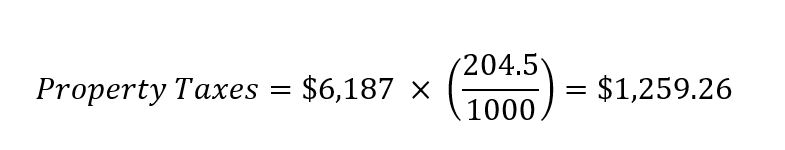

A city commission passes a $32,675,419 budget for the year. With total taxable property value of $159,782,000, the city taxes properties at 204.5 mills to generate the required revenue.

For a property with a taxable value of $6,187, the owner pays $1,265.24 in city taxes:

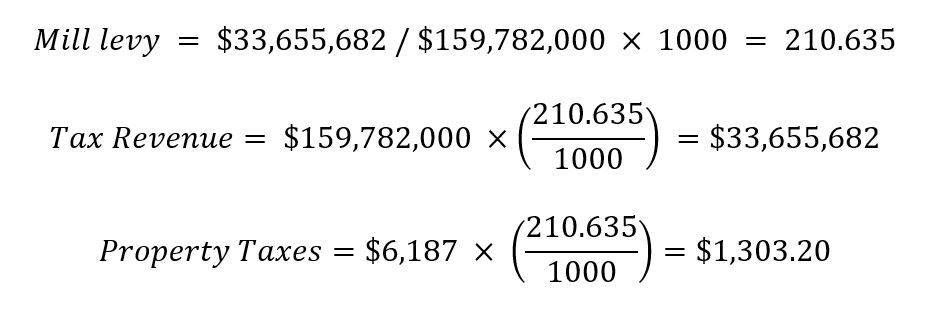

If the city’s budget increases by 3% to $33,655,682 ($32,675,419 x 1.03), the mill levy increases to 210.635 and the property owner now pays $1,303.20 in taxes:

3. Overall Property Values Rise with Fixed Mill Levies

As mentioned earlier, rising overall property values don’t directly increase taxes for mills that adjust. However, when a mill levy remains fixed, increases in taxable value will lead to higher property taxes. This is effectively an increase in existing government spending.

Example

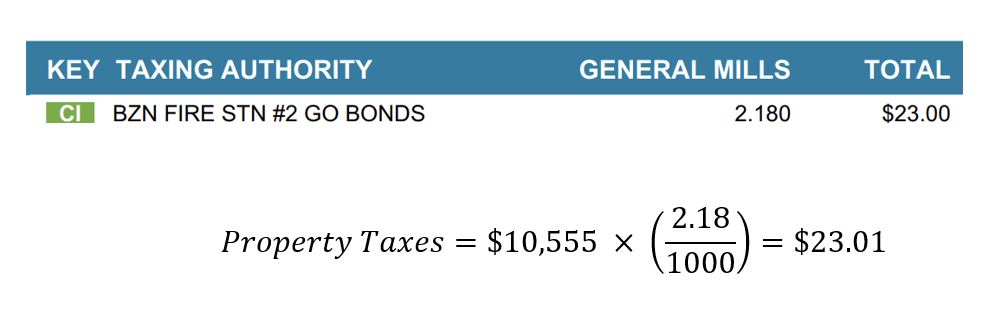

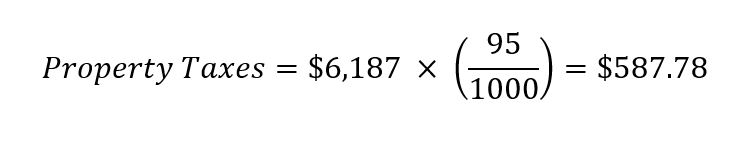

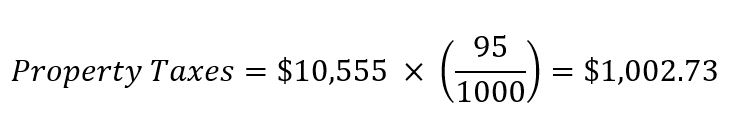

Let’s use the 95 Mill Levy as an example to demonstrate how property taxes increase with fixed mill levies. The example property has a taxable value of $6,187, resulting in $587.78 in taxes for the 95-Mill Levy:

If the property’s taxable value increases to $10,555, the taxes rise to $1,002.73:

As a result, property taxes increase from $587.78 to $1,002.73, a $414.95 increase due to the fixed mill levy.

4. Your Property’s Value Increases While Others’ Values Hold Steady

When your property’s taxable value increases but others’ do not, your taxes rise while others’ may decrease to balance the overall tax revenue.

Example

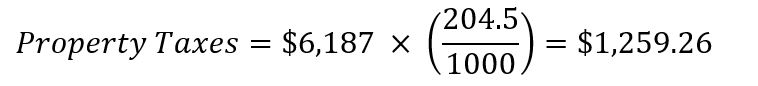

Suppose a city commission passes a budget of $32,675,419 for the year. With a total taxable property value of $159,782,000, the city taxes properties at 204.5 mills to generate the needed revenue. For a property with a taxable value of $6,187, the owner would pay $1,259.26 in city taxes:

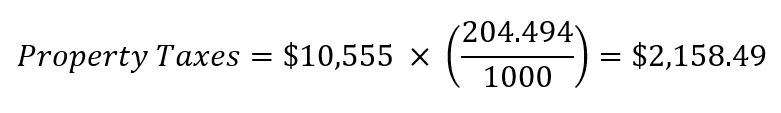

The property’s taxes now increase to $2,158.49:

As a result, property taxes rise from $1,259.26 to $2,158.49, an increase of $898.84.

5. Your Property’s Value Holds Steady While Others’ Values Decline.

Even if your property’s taxable value remains the same, your property taxes can still rise if others' taxable values decrease.

Example

A city commission passes a budget of $32,675,419 for the year. With a total taxable property value of $159,782,000, the city taxes properties at 204.5 mills to generate the needed revenue. For a property with a taxable value of $6,187, the owner would pay $1,259.26 in city taxes:

Now, if a large corporation’s taxable value within the city drops by $50,000,000, the total taxable value within the city decreases to $109,782,000 ($159,782,000 - $50,000,000). To maintain the same revenue, the city would need to increase the mill levy to 297.639:

As a result, the property’s taxes would now increase to $1,841.49:

It's important to note that if your property’s taxable value remains unchanged but new properties are added to the tax base, the total taxable value increases. This could result in a decrease in your property taxes, provided the government’s budget remains the same. However, in many cases, government budgets increase as additional properties are added.

6. Special Assessments Increase

A property tax statement may include special assessments—additional charges imposed by a tax jurisdiction to fund specific public projects or services that directly benefit the property. These are often flat fees added to the overall property tax bill.

When special assessments increase, property taxes rise accordingly.

Example

A county introduces a new Conservation District assessment of $5.07 per property owner.

As a result, each property owner's taxes increase by $5.07.

How Do I Determine What Caused My Property Taxes to Increase?

This post outlines six mechanisms that can cause property taxes to rise. If your property taxes have increased, it is due to one (or several) of these factors. To pinpoint the source(s) of the increase, compare your current year’s tax statement to last year’s.

- Ignore the mill rates, as they aren’t directly comparable across years.

- Focus on your property’s market value, and taxable value, and review the line-item levies and special assessments.

Consider These Questions:

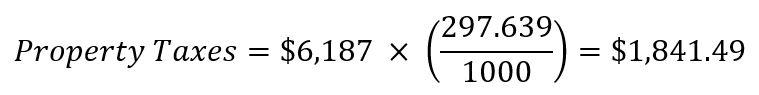

1. Did my market value or taxable value increase?

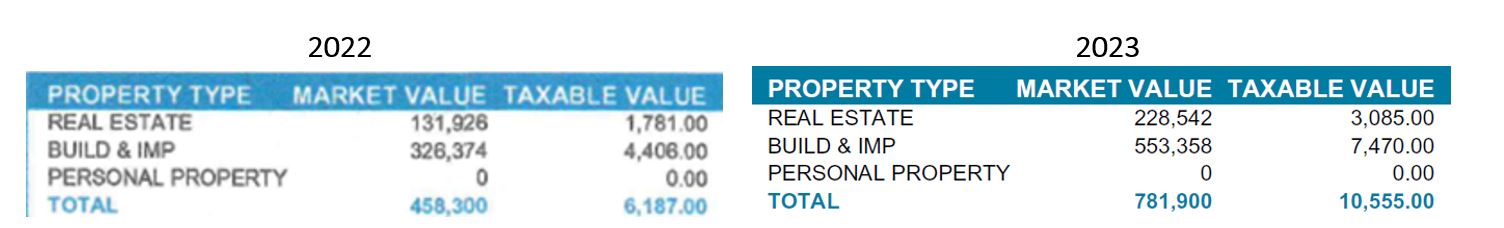

2. Are there any new line-item levies on my property tax statement? These are often marked with an asterisk (**).

3. Have there been increases in existing government spending, as reflected in the line-item levies?

4. Are there any fixed mill levies?

5. Was there any change in special assessments?

Example

For the example property:

1. The market value and taxable value increased from 2022 to 2023.

2. Four new line-time mills were approved by voters in 2023.

- Governments increased their existing budgets.

- The city, county, and school district expanded their budgets.

- The State’s fixed mill levies increased government spending.

- Very little change to Special Assessments, see OTHER.

Footnotes

a Every property in Montana is subject to the 95-Mill Levy for public school district equalization with few exceptions. The 95-Mill Levy is divided into 33 mills for elementary schools, 40 mills for aid, and 22 mills for high schools.

b This change isn’t exact because the taxable value wasn't perfectly held constant. However, it's close, as property values in Bozeman were relatively stable, with most properties experiencing similar value increases.

c Rounding differences typically $0.01 are common.

This is Part 2 of a Series on Property Taxation in Montana.

Greg Gilpin

Professor