Today marks the first day of the new water year, which runs from October 1 of each year through September 30 of the next. Water managers

count time using the water year because after Oct. 1, precipitation no longer matters

so much for this year’s crops – instead, most of it will be stored in reservoirs and

snowpacks and be used during next year’s growing season.

Likethe calendar year New Year’s Day, the start of the new water year represents a fresh

start and hope that next year can be better than the last. And this last water year

was bad – by some measures, it was the worst drought in history. So let’s take stock

of where we stand up here in Montana and how things look for the future.

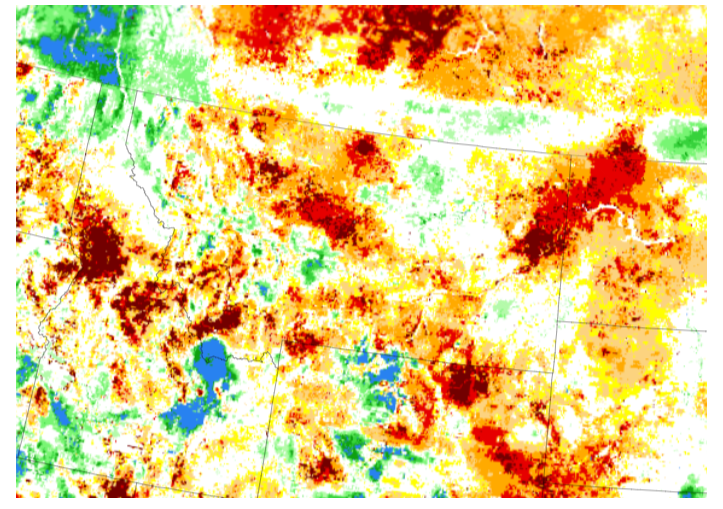

Currently, theentire state of Montana is still in severe drought or worse, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, and about two-thirds of the state is in “extreme” or “exceptional” drought. This

has been especially bad for dryland agriculture – farming and ranching that isn’t

irrigated. Precipitation has been especially scarce in the major agricultural areas

of Montana, with many weather stations reporting total water-year precipitation at less than 50% of normal.

Irrigatorsmay have been more fortunate, though. The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

shows that most major watersheds feeding Montana have had precipitation between 80 and 100% of normal. In other words,

we have had rain and snow in the mountains, so if you have access to water in the

rivers and reservoirs, you might have been all right this year.

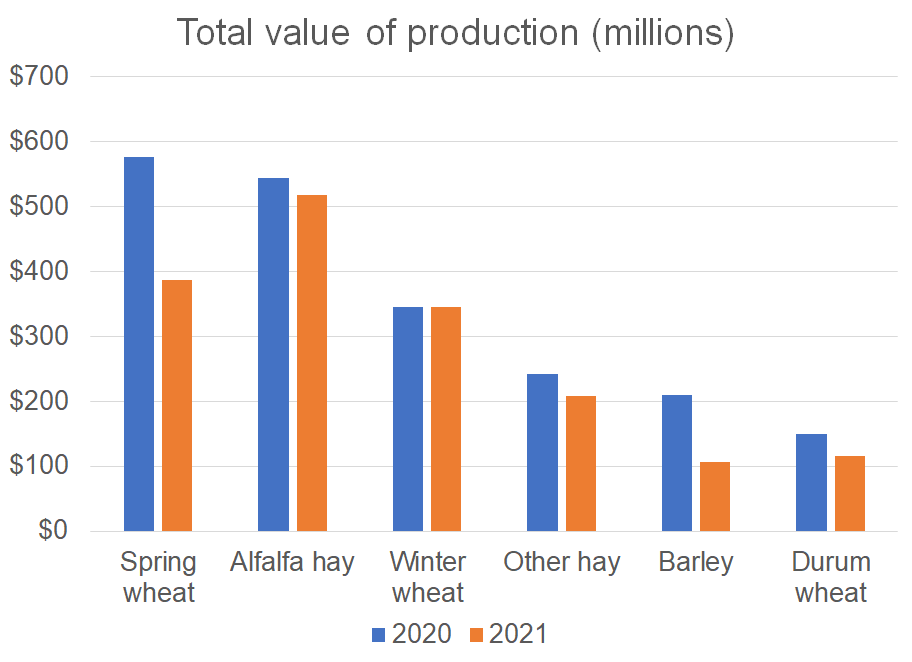

Crop production has taken a nosedive. The USDA National Agricultural Statistics Services

shows that crop yields for all major crops in Montana are around half of what they were in 2020. But what’s

interesting is that prices are way up. Because the drought hit much of the country, not just Montana, yields everywhere

are down. And – think back to Econ 101 for a second – when supply shifts inward but

demand doesn’t change, prices rise.

The result is that higher prices have compensated for lower yields, and crop revenues

haven’t actually changed very much. The graph here shows the total value of production

for the six biggest crops in Montana. Spring wheat and barley revenues are down somewhat,

but hay and winter wheat are pretty steady. (These are my own calculations using the

two NASS reports linked in the previous paragraph).

Now, not all producers may have been able to take advantage of the price increases, for example if they locked in contract prices earlier. But high rates of participation in crop insurance and expanded access to federal disaster assistance have provided extra help. Even though it’s been a tough year, most farmers have likely been OK financially.

What’s the outlook like for the new water year? Montana’s reservoirs look like they’re

in pretty good shape, unlike other parts of the west, like California and Oregon.

The NRCS shows that although some reservoirs are a little low, many are at or exceeding 100%

of normal for this point in the year. This “carryover” storage should provide something

of a backstop for irrigators and municipalities moving into the new water year.

Soil moisture, on the other hand, is in bad shape. The National Weather Service shows that most of Montana is in the 10 percent of worst years for soil moisture in history, and some parts are in the 1 percent worst ever. Soil moisture in the deeper root zone is not nearly as disastrous as it seems at the surface, according to data from NASA’s GRACE satellites, but it’s not doing great either. Soil moisture can recover if we get more rain this fall, but the huge deficit means it will take more moisture to recover than usual.

This water year was bad, but unfortunately, we can expect to see droughts get worse

in the coming decades, as the Montana Climate Assessment tells us. One response in the right direction may be the recently-announced effort to update the Montana Drought Management Plan. It’s only going to become more important to

prioritize investments and research that can improve adaptation and drought resilience.

It’s also equally important to reduce the ultimate drivers of the changes we’re seeing

– emissions of greenhouse gases.

See other Related Articles:

Drought Resource Update

Nick Hagerty

Assistant Professor

nicholas.hagerty@montana.edu