Businesses throughout the country are still struggling to fill job vacancies. Numerous factors are responsible for the tight labor market. The retirement rate of older workers rose in 2021, and workers retired at younger ages. Many workers reassessed their career aspirations and priorities before returning to the workforce following layoffs in 2020. Worker burnout increased among frontline workers and caregivers especially, and some of these workers have not returned to the workforce. Workers are also reshuffling between jobs in the same sector or between sectors. In November 2021, hiring rates exceeded quit rates in many sectors, and employers in sectors with some of the highest quit rates are raising wages and increasing employee benefits (Fuller and Kerr, 2022).

Another important factor in the tight labor market is the recent decline in immigration. Immigration has been falling since 2016 and dropped precipitously in 2020. Much of the pre-pandemic decline in immigration can be attributed to changes in immigration policies, tightening border enforcement, and reduced Mexican-U.S. migration (Peri and Zaiour, 2022). Immigration has recovered somewhat from border closures implemented during the pandemic, but still lags pre-pandemic projections. State-level analysis shows that reduced migration from 2017-2021 increased the ratio of job vacancies to unemployed workers by 5.5 percentage points (Duzhak, 2023). Effects of decreased immigration is not uniform across industries. Industries that had a 10% higher dependence on foreign workers than another industry in 2019 had 3% higher job vacancies in 2021 (Peri and Zaiour, 2022). The rate of unfilled jobs in food and hospitality industries remains high today.

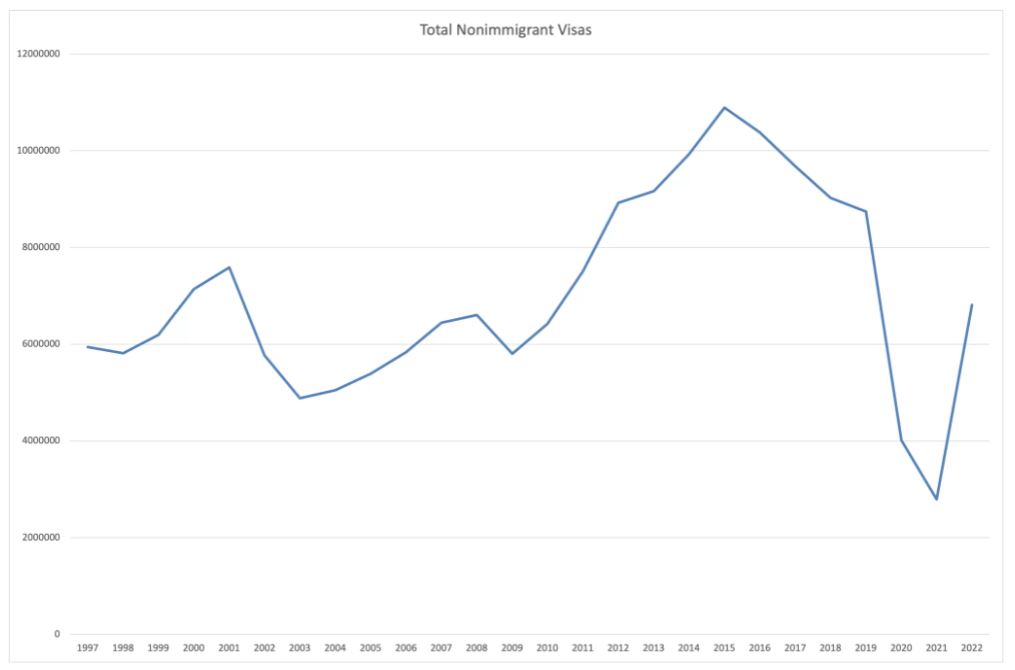

Figure 1 shows that total nonimmigrant visas issued by the United States has been declining since 2015, dropped precipitously in 2020-2021, and only partially rebounded in 2022. Many of the workers and students on these visas are highly educated and contribute important skills to the economy. It is estimated that there were 2 million fewer working-age immigrants in the United States at the end of 2021 than there would have been if pre-2020 immigration trends had continued. 1 million of these immigrants would have been college educated (Peri and Zaiour, 2022).

Figure 1. Total Nonimmigrant Visa Issuances

Data Source: U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs

Immigrants contribute, not only to the workforce, but also to research and development, entrepreneurship, and the creation of new jobs. If reduced immigration causes any of these outcomes to decline, there could be longer-term negative economic consequences. Policymakers might need to consider carefully the roles of immigrants in the U.S. workforce and economic growth, especially as baby boomers in the domestic workforce continue to retire.

Works Cited:

Duzhak, Evgeniya A. 2023. “The Role of Immigration in U.S. Labor Market Tightness.” FRBSF Economic Letter (February 27) Accessed https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2023/february/role-of-immigration-in-us-labor-market-tightness/ Accessed October 3, 2023.

Fuller, Joseph and William Kerr. 2022. “The Great Resignation Didn’t Start with the Pandemic.” Harvard Business Review (March 23) https://hbr.org/2022/03/the-great-resignation-didnt-start-with-the-pandemic Accessed October 3, 2023.

Peri, Giovanni and Zaiour, Reem. 2022. “Labor Shortages and the Immigration Shortfall” Econofact (January 11). https://econofact.org/labor-shortages-and-the-immigration-shortfall. Accessed October 3, 2023.

See other Related Articles:

Tight Labor Markets and Immigration

Is H-2A Reform Possible? And What Would It Mean for Workers and Employers?

Help Wanted & H-2A

Diane Charlton

Associate Professor